- Home

- Gary Imlach

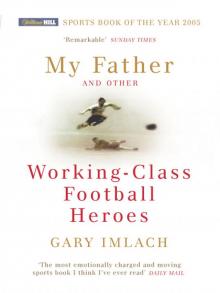

My Father And Other Working Class Football Heroes Page 8

My Father And Other Working Class Football Heroes Read online

Page 8

For me the most precious object in the cabinet is a football. Yellow with white laces and a desiccated bladder rattling inside, it was last kicked in October 1957. I’m not the only person who would think it valuable: in black ink on the leather panels are the signatures of the Busby Babes, fresh out of the bath in the away team dressing room. The game had been so sublime that Forest’s trainer Tommy Graham had asked both sets of players to sign the match ball.

My father’s autograph is there, compact and slanted, in his playing position – up in the top left corner of a panel that the centre-forward Tommy Wilson has signed bang in the middle. The only questionable signature is Matt Busby’s. Instead of black ink it’s in green Biro, with his title, ‘manager’, in brackets underneath. It’s too ludicrous to be a forgery, so perhaps the fountain pen ran out, or one of the United players held onto it after he’d signed and Tommy Graham was left scrambling for whatever came to hand when the great man emerged. The Forest trainer gave the ball away to be raffled at some fundraising event or other and it had come back to the club on permanent loan from the family of the winning ticket-holders.

Coming early in the season, the match itself decided nothing, led to nothing, wasn’t a turning point or a launch pad for either side; it was a league game, one of forty-two. Yet without the leverage of significance, it became a classic. Not years later, once the selective collective memory had edited it down into twenty minutes of brilliantly flickering highlights, but instantly and universally. It must have been an extraordinary match.

1957–58 was my father’s third season with the club. Forest were newly promoted from the Second Division, Manchester United were the defending champions. The newcomers had made a great start – they were level on 17 points with United, the pair of them lying third and fourth in the league. For the Forest players the visit of the Busby Babes would have been like getting their first-class ticket punched, validation of their arrival in the top flight.

The same seems to have been true for the spectators. On the day of the game the queues outside the City Ground began at eight in the morning. An hour before kick-off there were more than 47,000 fans inside, 3,000 on the running track around the pitch because there wasn’t room on the terraces. Benches were brought over from the cricket ground at Trent Bridge to seat them. The weather was implausibly warm and sunny for mid-October. Then the game began. The match reports were uniformly rapturous, a media conspiracy of praise and enjoyment. They read like a sort of nostalgia for the present, as if the entire press box had been briefed on the strictly embargoed knowledge that games like this wouldn’t be around for much longer. As though some kind of pre-Munich heightening of the senses had sharpened everyone’s appreciation for the simple beauty of a well-played game of football.

One of the best accounts of the match appeared in the Manchester Guardian, under the byline ‘Old International’. The writer was Don Davies, who would die four months later in the crash at Munich.

For one traveller at least this was the perfect occasion; a case where the flawless manners of players, officials and spectators alike gave to a routine league match the flavour almost of an idyll.

There was the tingling sense of a great occasion . . . Rarely, if ever, has expectation of a football treat been more thoroughly roused; rarely, if ever, has it been so quickly and completely satisfied.

Before play had been in progress five minutes one could detect the four cornerstones of Forest’s recent successes. These were, in emergence, the two wing half-backs, Burkitt and Morley, the veteran schemer and strategist Baily, and that bundle of fiery endeavour with a keen football brain and a long, raking stride, Imlach.

He has a strongly marked gift for intelligent roaming, in pursuance of which he once crept up behind Blanchflower unawares and gave that Irish international the shock of his life by suddenly thrusting a grinning face over his shoulder, the while he nodded a long, high centre from Quigley unerringly home.

That headed goal from my father just after half-time was Forest’s equaliser, Liam Whelan having put the visitors ahead early in the game. Twelve minutes later Dennis Violet scored again for United and, despite a last half-hour of sustained home pressure, 2–1 was the final score. Afterwards the managers, the players and the press lined up to pay tribute to themselves, each other and the game. ‘I’ll have to cast my mind back some way to recall a game as good,’ declared Matt Busby, who had just led his team to successive League Championships and into the European Cup. ‘Give me such matches and I might forget we didn’t get the points,’ said the Forest manager, Billy Walker.

Frank Swift, the legendary Manchester City goalkeeper turned sportswriter, summed up in the News of the World the following day: ‘The luck then to United. The glory to Nottingham Forest. And my thanks to both teams for a match which was a credit to British football.’

Wow. I’d always thought of the 1959 FA Cup Final as my father’s finest hour – hour and a half – and the ’58 World Cup in Sweden as his biggest honour. I’m certain that he had too. But World Cups and FA Cups were special by definition. They were what players strived for. Games like this one were what they played for, the reason they played at all. Not for the glory or the win bonus, but for the simple routine joy of it. Careers only consist of highlights in retrospect; in real time they’re a rolling, rhythmic continuum: this week, next week, midweek. And for my father this game against Manchester United was on a direct line stretching all the way back to the ones on the square in Lossiemouth. The crowd was bigger and the setting grander and everybody’s kit matched, but the elements that mattered were all the same.

I hadn’t consciously made the connection before, but as I read about the United match my mind leaped forward too – to the 1990s when I was in America covering the NFL. The coach of the Buffalo Bills, Marv Levy, was a man of my father’s vintage who was perpetually being beaten by Manchester United, or the gridiron equivalent. His teams went to four Super Bowls and lost them all. But that’s not what sparked my memory of him. It was what he used to say to his players as they emerged from the locker room before a game: ‘Where else would you rather be?’

Pre-season, play-offs, Super Bowl, it didn’t matter to Marv – or rather it all mattered equally: ‘Where else would you rather be, men – than right here, right now?’ Compared to the chest-beating war cries we heard every week on the satellite feed from NFL Films it sounded refreshingly old-fashioned, like something out of a 1940s film. It became an office catchphrase, wearily ironic in an edit suite of empty pizza boxes at two in the morning. We held Marv in great affection – we used him as a guest on live shows – and sent him up only gently, with respect. He was from a different generation to ours, and two generations removed from some of the young millionaires in his team. His unabashed sincerity seemed anachronistic, at odds with the brash mayhem of the modern game whooping and hollering its way past him towards the field, even as he offered his decent man’s reminder to savour the privilege of being paid to play.

I think now that we were – I was – secretly embarrassed at how deeply he touched us with that rhetorical question. How he cut through the accumulated layers of cynicism that had formed since childhood into a thick crust over our enjoyment of sport, with a simple enquiry. I suspect the effect was the same on his team, regardless of age, race, social background or tax bracket. ‘Where else would you rather be?’

My father never needed to ask himself the question. For the fourteen years of his playing career Saturday afternoons were taken care of. Whatever else might be happening in his life, personally or professionally, there they were at the end of the week, focal points of pure purpose.

When Crystal Palace released him in his thirties and he signed on for Dover and then Chelmsford in search of a game, a reporter asked him whether the Southern League wasn’t perhaps a bit of a comedown for an ex-international. ‘Bloody idiot,’ he said, relating the story to my mother when he got home. He wouldn’t have recognised the premise of the reporter’s question. If you cou

ld play and you had the opportunity to play, why wouldn’t you play? What else would you rather do on a Saturday instead? Where else would you rather be? I envied my father his certainties back down the decades. By the time I was in my thirties, Saturday afternoon had long since become the same shaped hole as Sunday, or – once I’d escaped my last newsroom and started working from home – any other afternoon of the week.

Christ, what a life. No wonder the clubs got away with treating players as slaves for so long. If bondage meant being forced to play Manchester United in front of 47,000 people, who in his right mind was going to volunteer for the escape committee?

That an unfashionable team like Forest, fresh out of the Second Division, could credibly take on the Busby Babes at their own beautiful game was in many ways thanks to the maximum wage and the hated retain-and-transfer system. Together they created a labour market that was a model of equal opportunity – but only for the clubs.

The low ceiling on players’ earnings meant that a solvent Second or even Third Division outfit could match the wage scale of the top teams, where not everybody was on the maximum anyway. In fact, with appearance money making up a sizeable chunk of a player’s weekly wage, there was every chance that he’d be better off playing regularly in the Second Division than turning out for the reserves at a club in the First. And if a player could legally earn no more at Old Trafford than he could down the road at Bury’s Gigg Lane, or the City Ground in Nottingham, the financial imperative for moving to a bigger club was removed. Of course, there was always personal ambition – but retain-and-transfer took care of that.

The Nottingham Forest team that ran out to face Manchester United in October 1957 was undoubtedly a good footballing side, but in most other respects about as far from the ethos of Busby’s carefully nurtured Babes as it was possible to get. Instead Billy Walker, a former England international and already a successful manager at Sheffield Wednesday, had assembled a sort of Magnificent Eleven: an unlikely blend of veterans, cast-offs, stars the bigger clubs thought were past their prime and younger players who, for one reason or another, hadn’t realised their full potential elsewhere. It was as one of the last on this list that my father had arrived by train from Derby in 1955, to be met by the manager’s assistant, Dennis Marshall.

‘I’d just got in the office and I was taking my bicycle clips off when Billy Walker came in and said, “Don’t take them off, I’ve got a little job for you.” I said, “Do I get any taxi money? It doesn’t make much of an impression, me arriving with me bike clips,” and he said, “No, leave your bike here – get a bus from Trent Bridge.”

‘This lady came out first looking a bit flustered, and I was standing there holding a tin of paint because I’d had a bit of time to spare on the way up there. We started talking and I said, “I don’t know what Billy Walker has told you about Nottingham Forest but we’re not rich.” Your mum said, “I don’t care, we’ve got to get away from Derby.” Then she told me the story – so I must have been the first person in Nottingham to know the business about the handbag.

‘Foolishly, I caught a bus that terminated on the other side of the river. So there I am crossing Trent Bridge with a pot of paint trying to shepherd this handsome-looking couple to the ground, telling them, “Here’s the Trent,” like a tour guide. I took them into the boardroom and Billy Walker took them to lunch – which was very rare for him – and signed your father. I remember I had to type the forms up quickly because it was very close to the start of the season.’

Dennis Marshall is the curator of Nottingham Forest’s anecdotal history. He could just as easily have been a sports journalist as a sports administrator, and he could just as easily have been a jazz journalist as a sports journalist. In fact, to start with he could well have been Forest’s goalkeeper, had it not been for a bullet in the leg during the Second World War. He’d been at the club in various capacities since leaving school at the age of thirteen, finally settling into the custom-made post of personal assistant to Billy Walker, where he patrolled the swampy territory between what the manager told his players and the truth.

Since my father had no control over who bought his registration and where he was sent to play, all he could do was hope that Nottingham Forest would turn out to be a happier club than Derby. Dennis Marshall, with his tin of house paint and his bus fare for three out of petty cash, was the first sign that it would. Dennis’s wife – Auntie Jean and Uncle Den, we grew up calling them – had the same-sized feet as my father and used to break in his new boots for him, unscrewing the studs and wearing them to do the housework until they were soft enough to spare him the usual blisters. When Forest signed Jeff Whitefoot one close-season, it was my father who scaled the locked gates of the City Ground after Dennis realised that the keys to the Whitefoots’ club house had been left in the deserted offices.

As I did the rounds of my father’s surviving teammates, the one word that kept cropping up in relation to Forest was ‘homely’. It was a small, friendly club, not long out of the Third Division when he arrived, and unique in the league in that it wasn’t a limited company. It was run by amateurs, a committee of local worthies and businessmen, rather than an autocratic chairman who might view it as an outpost of his personal fiefdom. It could be a shock to the system for players coming from the upper echelons of the League. Chic Thomson, a clever and commanding goalkeeper, arrived from Chelsea in 1957 with a championship medal and a stronger sense of his own worth than some of his new teammates.

‘I remember my first experience of travelling away with Forest. We had third-class return tickets. Bill Whare and I were going down the carriage saying to people, “Excuse me, excuse me – are these seats free?” We got it changed, a few of us, when we saw Rotherham were going north in the dining car and we were hunting for seats.’

Chic Thomson was one of a few shrewd buys that Billy Walker made on promotion to the First Division. To help get Forest out of the Second the season before, he’d flown in the face of opinion around the League to sign an ageing ex-international most people thought was ready for retirement.

Eddie Baily had been a brilliant inside-left both for England and the Spurs championship side of 1951. When Forest approached him five years later he was still in London, driving a three-ton truck and playing for Port Vale. ‘I used to train in the morning at Leyton Orient, deliver these copper sheets in the afternoon, then go up on a Saturday to Port Vale and play,’ Eddie told me, as though he were finally free, years after the fact, to let me in on the details of a fabulous con trick. He did pretty much the same for Forest, turning up at the Trent Bridge Inn on a Saturday just in time for the pre-match meal, then turning out, bandy-legged and balding, a few hours later to provide my father with the finest service of his career.

Along with having no real control over where he played, as a winger my father had only a limited amount over how well he was able to play. In the W formation of the ’50s, the winger’s job was to hug the touchline and wait to be fed. His inside-forward could make or break him. Just before Christmas 1956 Baily took over at inside-left when Billy Walker’s other commuting veteran, the former Arsenal star Doug Lishman, missed his train. Over the next eleven games my dad scored ten goals and Forest racked up seven consecutive wins, dropping only two points between the New Year and March. It was enough to take them up.

‘He done my running, bless his heart. Your dad was quick and he had a tremendous left foot. I was used to great wingers, I used to play with Les Medley who played for England with me – we represented England as a club pair. Your father was a similar type to Les. All my wingers got caps, I made ’em all internationals.’ Eddie’s cockney music-hall boasting is so matter of fact it almost sounds like modesty. But when he won his first Scotland cap the following season my father went out of his way to credit the contribution of his old inside-forward partner. By then, though, Eddie Baily was gone. Billy Walker had promised him and Doug Lishman under-the-counter payments of £400 if Forest were promoted. He hadn’t del

ivered, and the two of them had confronted him.

‘It was on a personal handshake between us. But when the time came he talked his way out of it – “It’s illegal . . . I’ve been in the game a long time . . .” Yeah, that don’t make no bleedin’ difference. Doug was saying, “I’ll kill the bastard.” He was very upset. He was going to retire, start a little antiques business in Stoke, he said the money would come in handy. I wanted to re-sign, so I didn’t want to make a fuss. In the end, the chairman got to hear about it and shortly into that season old Bill decided I’d be better off out of the way. That’s when I signed for the Orient, which suited me – it was only a hundred yards from where I lived.’

Billy Walker may have promised illicit bonuses, but at Nottingham Forest he wasn’t in a position to pay up. Even if he’d been able to get them sanctioned by the committee that ran the club, Forest had perhaps the most scrupulous secretary in the Football League. Noel Watson was an FA councillor, chairman of the FA Cup Committee, a qualified referee and a Justice of the Peace. Unmarried, his life dedicated to the game and to the club, he was the straitlaced yin to Billy Walker’s slightly crooked yang.

My Father And Other Working Class Football Heroes

My Father And Other Working Class Football Heroes